Following are random page extracts covering Thomas

Massey’s transportation to Australia. The aim is to

relate something of the writing style and content.

Example Text Extracts from Chapter 1

24

25

© Rutherford J Browne 2018

This site and book are protected by copyright. All or parts of it may not be copied or disseminated in any way

without the permission of the copyright owner. You may copy, reference or quote small sections of the work as long

as due acknowledgement is made.

THOMAS MASSEY TRIAL & TRANSPORTATION TO

AUSTRALIA

Transported HMS Gorgon 1791

Thomas Massey was committed for desertion as a soldier in the 47th Regiment (given a life sentence for desertion) and then charged in company of two others with breaking and entering the house of “ Thom. Hammon” near Knutsford in 1789. Massey was not charged with the act of burglary, but with being in the company of two felon burglars. One stole a shirt, value 5 shillings, from Hammon’s house. Massey was sentenced to death at Chester, England on 3rd Sept 1789. Sentence was reprieved on the condition of transportation for life. [See Appendix 1 for more detail - Mackenzie (2005)] It is hard to know the real circumstances behind Thomas Massey’s charge of desertion. His actions in later life, his respect for authority, his early pardon and his later generous donation to the Widows of Waterloo and the Crimean Patriotic War Fund do not fit the pattern of a soldier who hated army life and tried to run from service. Thomas liked his drink and it was more likely he overstayed his leave, or he may have been the victim of a disciplinary example, or a lark gone wrong. The real circumstances we will likely never know, but there is little doubt his service record and the reason for the desertion charge would have been thoroughly investigated by Governor King in 1800 and Governor Macquarie in 1810 and it would seem, from their actions, Thomas met with their approval on both occasions.“Better to be born lucky than rich!”

So goes the old saying that my mother was always quoting. It had its roots in Massey family mythology and seems to me likely it was often quoted by Thomas himself. Thomas Massey sailed along with 29 other male convicts, from Spithead, the 15 March 1791 on board the Royal Navy Frigate HMS Gorgon . The Gorgon was one of eleven vessels of the Third Fleet and was converted to bring out stores and provisions to the starving colony of New South Wales. Her lower deck guns were left in England and her complement reduced to 100 men including officers. No doubt Massey learned something about sailing – due to the reduced complement, the 30 male convicts assisted in working the ship. Also passenger on Gorgon was Philip Gidley King (2nd Lieutenant to Captain Arthur Phillip, HMS Sirius - First Fleet). King who had been sent by Governor Arthur Phillip to establish a colony on Norfolk Island had returned to England to report on the difficulties of the settlements at New South Wales. King was now returning on the Gorgon to take up his post as Lieutenant-Governor of Norfolk Island. King later became the third Governor of New South Wales on 28 September 1800, and was Governor from 1800-1806. King, like Arthur Phillip and later Macquarie, considered that ex-convicts should not remain in disgrace forever. He appointed emancipists to positions of responsibility, regulated the

employment

conditions

of

assigned

servants,

and

laid

the

foundation

of

the “ticket of leave” system for deserving prisoners.

The

journey

took

six

months,

in

a

wooden

vessel

some

150ft

(50m)

long.

King,

although

a

passenger,

was

a

trained

Naval

Officer.

Massey

although

a

convict

and

a

crewman

was

a

trained

and

experienced

soldier.

It

is

not

hard

to

imagine

their

paths

crossed

on

more

than

one

occasion.

In

view

of

the

rapid

preferment

Massey

later

received,

starting

with

his

conditional

pardon

in

1800,

it

is

logical

that

King

was

likely

to

have

formed opinions as to his character on the voyage out.

A Voyage Round the World, in the Gorgon Man of War

It is our luck to have a rare record of Thomas Massey’s long voyage to Australia. Command of Gorgon was given to Captain John Parker. Mary Ann Parker, his wife, sailed with him to Sydney and records the voyage in her 1795 book A Voyage Round the World, in the Gorgon Man of War. [Parker (1795)] She writes: “despite the first fortnight spent receiving a good seasoning and buffeting in the Channel, it was a good trip South.” Gorgon stopped first at Tenerife for nine days to resupply. Thomas by now, was becoming just one of the crew and enjoyed his share of work and the ribbing and skylarking that constituted the crew at play. Thomas had always had an eye for the ladies and found the Captain’s wife and Mrs King worthy of a quick glance whenever possible as they strolled the deck. He soon learned that Mrs. Parker was a most competent individual, with a cool judgement and a quick mind. He discovered she was fluent in Spanish and even heard her act as an interpreter from time to time. On 29 April they crossed the line and Thomas found himself a victim of a sort of baptism against which his convict origin offered no protection. As Mary Ann Parker writes: On the 29th we crossed the line, and paid the usual forfeit to Amphitrite and Neptune. Those sailors who had crossed the line before burlesqued the newcomers as much as possible, calling themselves Neptune and Amphytrite with their aquatic attendants. They have the privilege to make themselves merry ; and those who have never been in South latitudes purchase their freedom by a small quantity of liquor. But the sailor or soldier who has none to give is the object of their mirth ; and the more restive he, the more keen they are to proceed to business. A large tub of salt water, with a seat over it is placed in the fore-part of the ship, on which the new comer is reluctantly put— the seat is drawn from under him and when rising from the tub, several pails of water are thrown over him—he is then pushed forward amongst his laughing shipmates, and is as busy as the rest to get others in the same predicament. The next re-supply stop was St. Jago in the Cape Verde Islands just off the western coast of Senegal, itself the most westerly territory of continental Africa. Here Thomas learned from the gossip that soon circulated amongst the crew that even the might of the British Navy deemed it wise to restrict shore visits to St. Jago. The islands had been colonised by the Portuguese. They were a major operating centre for the slave trade … … ...

1. Convicts to a new life

The heavens open - an unforgettable welcome to a new land

On the night of 19 September 1791 at 8pm Gorgon was just past the northern headland of what is now Jervis Bay when they were hit by a “tremendous thunder squall attended with most dreadful lightening and constant heavy rain”. About half past eight the ship was hit by lightening. Mary Ann describes the event in detail. … “the lightning struck the pole of the main-top-gallant-mast, shivered it and the head of the mast entirely to pieces ; thence it communicated to the main-top-mast, under the hounds, and split it exactly in the middle, above one third down the mast; it next took the main-mast by the main-yard, on the larboard side and in a spherical direction struck it in six different places; the shock electrified every person on the quarter-deck; those who were unfortunately near the main-mast were knocked down, but recovered in a few minutes.” Hit by a fireball: … “this [the lightening] continued until about half past ten, when a most awful spectacle presented itself to the view of those on deck; whilst we who were below felt a sudden shock, which gave us every reason to fear that the ship had struck against a rock; from which dreadful apprehension we were however relieved upon being informed that it was occasioned by a ball of fire which fell at that moment. The lightning also broke over the ship in every direction : it was allowed, to be a dismal resemblance of a besieged garrison; and, if I might hazard an opinion, I should think it was [resembled] the effect of an earthquake. The sea ran high, and seemed to foam with anger at the feeble resistance which our lone bark occasioned. At midnight the wind shifted to the westward, which brought on fine clear weather, and I found myself once more at leisure to anticipate the satisfaction which our arrival would diffuse throughout the colony.”Thomas Massey arrived in Sydney September 1791

Just where Thomas was, when the lightening and fire ball hit the ship, and what thoughts ran through his head, will never be known, but he would have been awestruck, part relieved, part anxious, as, “in fine clear weather”, Gorgon slid through the gap in the sandstone cliffs into Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) one of the finest harbours in the world. The Gorgon arrived in Sydney Cove on the 21 September 1791. At the time the colony was suffering extreme privation, made worse by the non- arrival of Guardian, wrecked at the Cape of Good Hope. While 3 bulls, 6 cows, 3 rams and 9 ewes died on the passage, recent deaths aside, the crew, the convicts and the several passengers all arrived alive and well; due in no small part to the excellence of Captain Parker’s command. This is in sharp contrast to other ships arriving at the time. Many convicts were transported using private contractors, many of whom reduced rations to the bare minimum to increase profit. Contractors were paid a fixed rate per head by the government for each individual transported whether they arrived in the colony or not. Mary Ann Parker wrote, that her husband’s distress and disgust at the state of some of the arrivals would remain forever in her memory. He had told her “I visited the hospital and was surrounded by mere skeletons of men— in bed and on every side lay the dying and the dead. Horrid spectacle!”

1. Convicts to a new life

27

28

For

example

Albemarle

arriving

on

13

October

1791

bought

250

male

and

6

female

convicts.

Of

these

32

male

convicts

died

on

the

passage

and

44

were

sick

on

arrival.

Britannia

arriving

on

14

October

that

year

had

129

male

convicts

of

which

21

died

on

the

passage

and

38

were

sick

when landed.

Thomas

would

have

been

acutely

aware

that

he

was

lucky

indeed

to

have

made

his

trip

across

the

world

in

a

British

Navy

vessel,

as

a

member

of

the

working

crew

and

under

the

eyes

of

someone

as

important

as

King.

Was

it

luck,

or

was

he

picked,

or

a

volunteer?

Just

how

this

came

to

pass

would

be

a

story

worth

exploring.

In

any

event

it

seems

to

have

been

recognised

by

Thomas

as

the

start

of

a

new

life

and

there

is

nothing in the records to suggest he ever wanted to return to England.

Reflections on the voyage and a new life

For a short time after his arrival Thomas remained attached to the crew of Gorgon as the cargo was unloaded and repair of the lightning damage commenced. What he found on shore, was not at all what he expected. The crew of Gorgon were saviours who had bought much needed supplies to a starving colony. They were welcomed wherever they went. Captain Parker was a man held in high esteem and his wife was the talk of the town. All who arrived on Gorgon, convicts included, basked in the reflected glory of the association. For Thomas this was the first glimmer of the possibilities of a new life. He had arrived as a convict, initially unsure of the tyranny his sentence might impose, but he quickly observed, fellow convicts in the settlement happily involved in the daily aspects of colony business. He did know of the labour gangs used to punish repeat offenders and the stories of theft, treachery and brutality that led to hangings, but he learned also there were rewards for loyalty, honesty and hard work. As the weeks passed Thomas would have found some time to reflect on the last traumatic weeks of his voyage. The horror of the drownings in a cold heavy sea; the sudden and unexpected terror of the lightening strike; the fire ball in the middle of a wild unknown sea; the looming unknown of his sentence in a strange land. Slowly, he must have come to realise, it had all been like a baptism of fire. He had survived. He was being given a new start in life, and he resolved to make the best of it, come what may. He had learned so much. On Gorgon he saw the respect given to men of justice and principle. He observed the finer aspects of command structure. He thought again of the lessons learned in the Cape Verde Islands of the evils of slavery and how greed and treachery marched hand in hand. … He would apply what he had learned and build a better life.

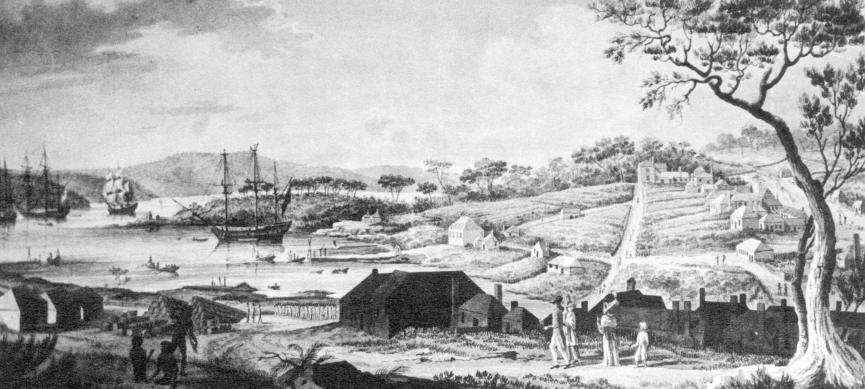

Sydney Cove as known to Thomas Massey 1793 – by Fernando Brambila

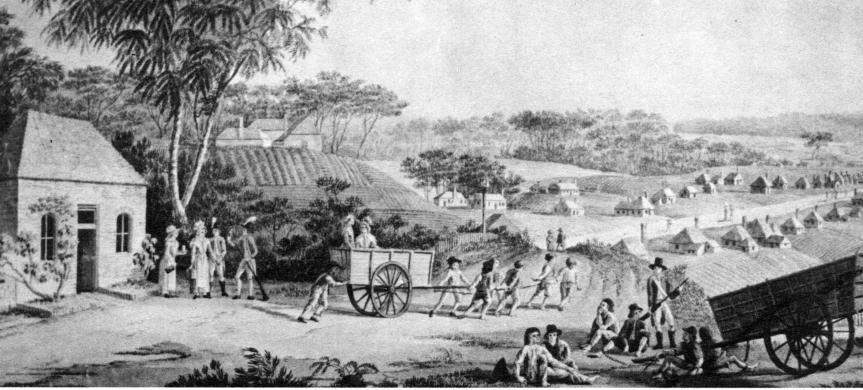

Parramatta as known to Thomas Massey 1793 – by Fernando Brambila

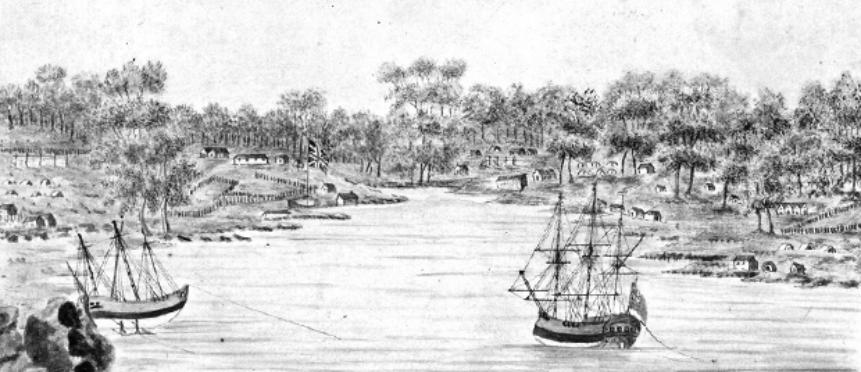

Sydney Cove c1791 at the time of Thomas Massey’s arrival in Australia

Watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley (Mitchell Library of NSW - Safe 1/14)

Thomas Massey and the first 50 years

of Launceston Tasmania -Biography

1. Convicts to a new life

1. Convicts to a new life

Early images of Sydney life c.1791-93

1. Convicts to a new life